On Disasters

An Opusculum on Cascading Failures

These principles apply to any type of disaster. I chose this instant winter storm because it is ongoing and therefore fresh in social memory.

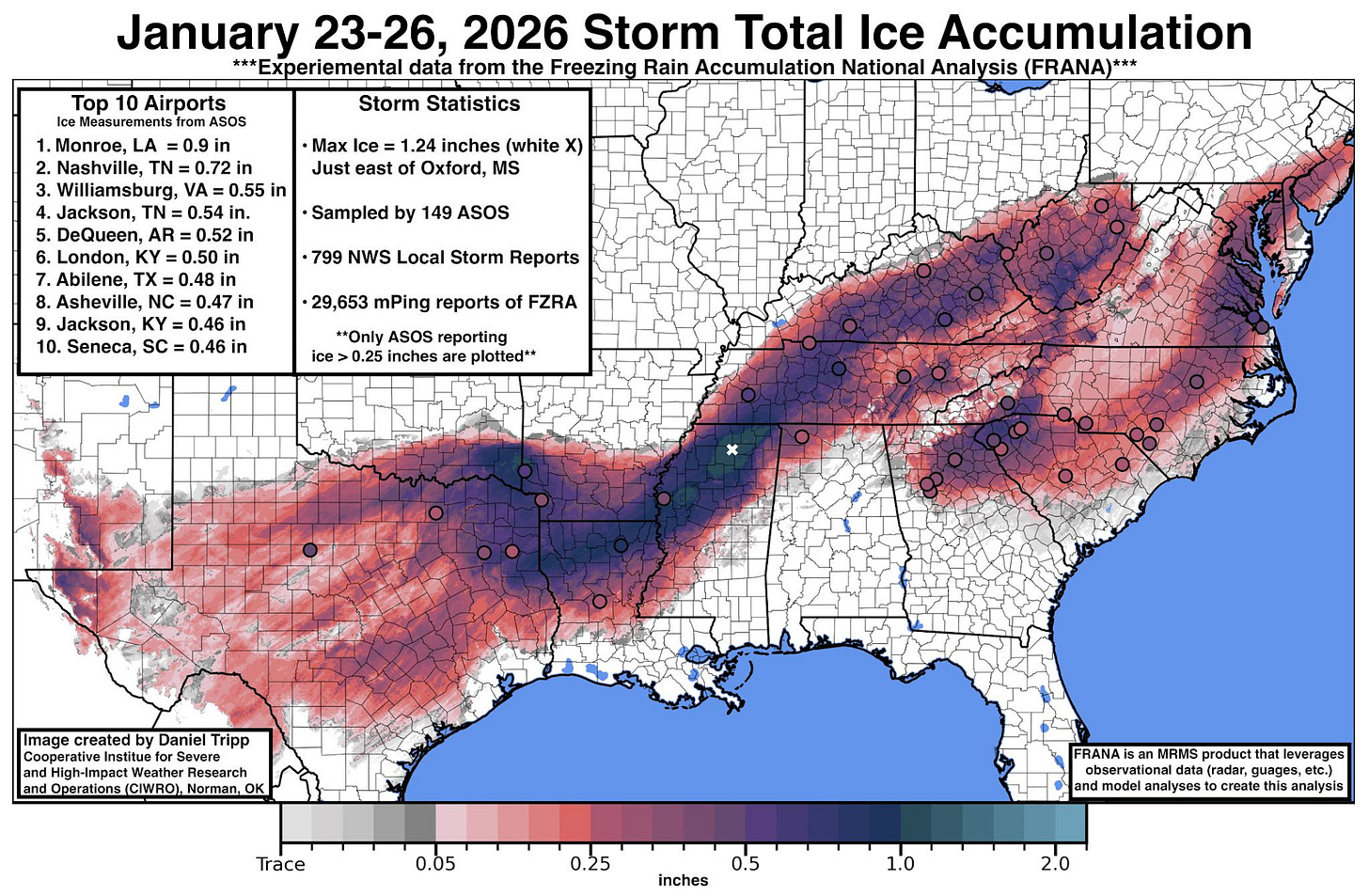

I’ve been monitoring a range of social media posts and comments in the last week after the Winter Storm of January 23-25, 2026, deposited several inches of sleet and freezing rain across Mississippi and a broad swath of the southern portion of the United States from Texas to the Mid-Atlantic coastal regions.

Many focus, rightfully so, on the state of preparedness (or lack thereof) for the transportation infrastructure, and of the extended power outages that persist. [One must wonder, however, where the power is coming from for these posts - likely the final percentages of a dying battery or a vehicle idling for heat - but that is a topic for another day.]

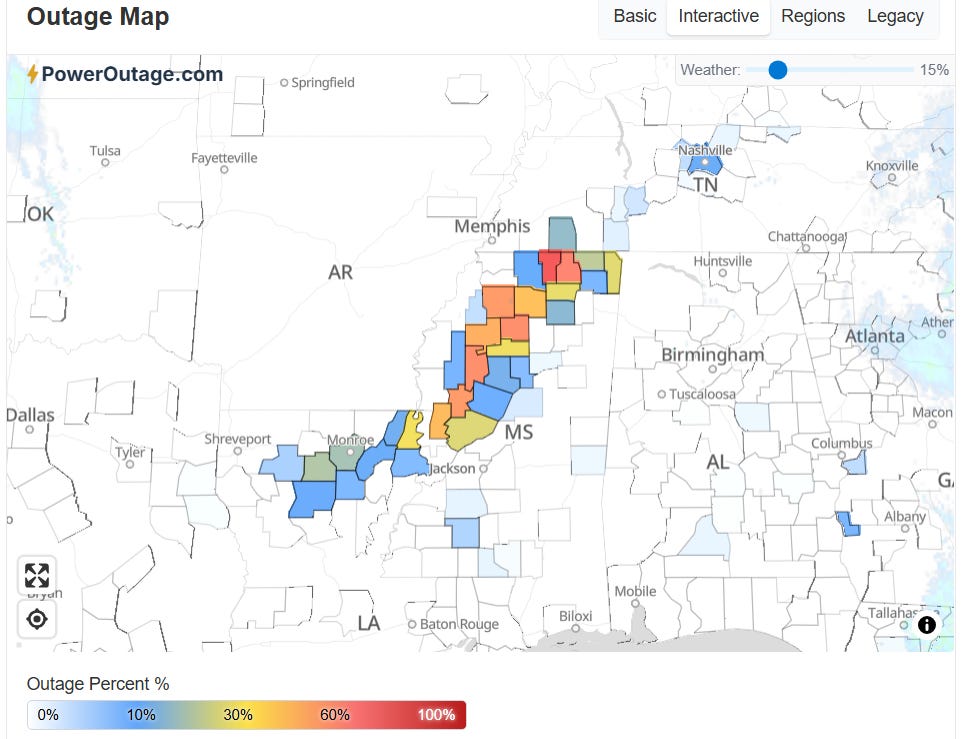

Widespread power outages occurred following catastrophic damage to transmission and distribution systems, with North-Central and Northeast Mississippi being the hardest-hit area. As of this writing some 68,000+ customers in Mississippi remain without power, seven days after the weather incident began. Some of those face an additional 7-14 day wait before seeing their power restored, while continuing to face temperatures near or below freezing.

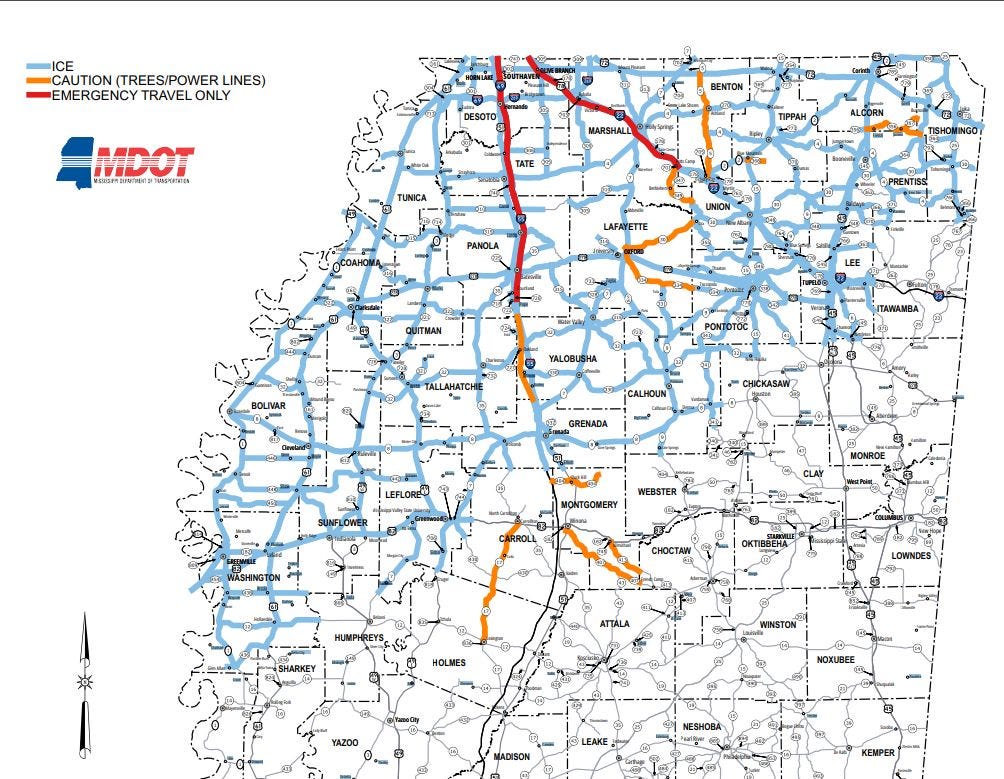

Primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary transportation corridors (Interstates, US Highways, State Highways, City/County streets/roads respectively) were significantly impacted across 25 counties in Mississippi (30% of the state’s counties). Complete stoppages reported on Interstate 55 and Interstate 22 in Mississippi with traffic gridlocked for dozens of miles, lasting several days.

Mississippi, while no stranger to winter weather and the occasional severe winter storm, is generally under-prepared for such, largely owing to our more temperate climate. Pure snow is a relative rarity; instead a more ‘wet’ mixture of sleet, snow and freezing rain is typically what can be expected. It is that ice accumulation risk that proves most difficult to mitigate against. We cannot simply bury tens of thousands of miles of electrical transmission and distribution lines. Having snow plows in reserve is prohibitively expensive given the relative rarity of need, and they’re simply ineffective against accumulations of ice that mimic the hardness of concrete.

Managing Emergencies

Since its inception in the 1940’s as Civil Defense, our nation has advocated for citizen preparedness as a shared local-state-federal responsibility. What began as an effort to prepare the nation for potential atomic or nuclear attack slowly grew to include natural disasters such as floods, hurricanes, severe weather and tornadoes. Over time more natural and manmade hazards were incorporated into community emergency plans, followed by post-incident recovery plans, and pre-event mitigation projects intended to lessen the effects of disasters. Emergency Management as a discipline and profession saw less of a clearly defined ‘birth’, and instead evolved slowly from those early Civil Defense efforts. As more hazards were brought into the planning spectrum, Emergency Managers pivoted to focusing on the various disciplines that were brought to bear in a response such as firefighting, law enforcement, communications, search & rescue, hazardous materials, etc. Today there are fifteen recognized Emergency Support Functions that form the backbone of local, state and federal disaster plans.

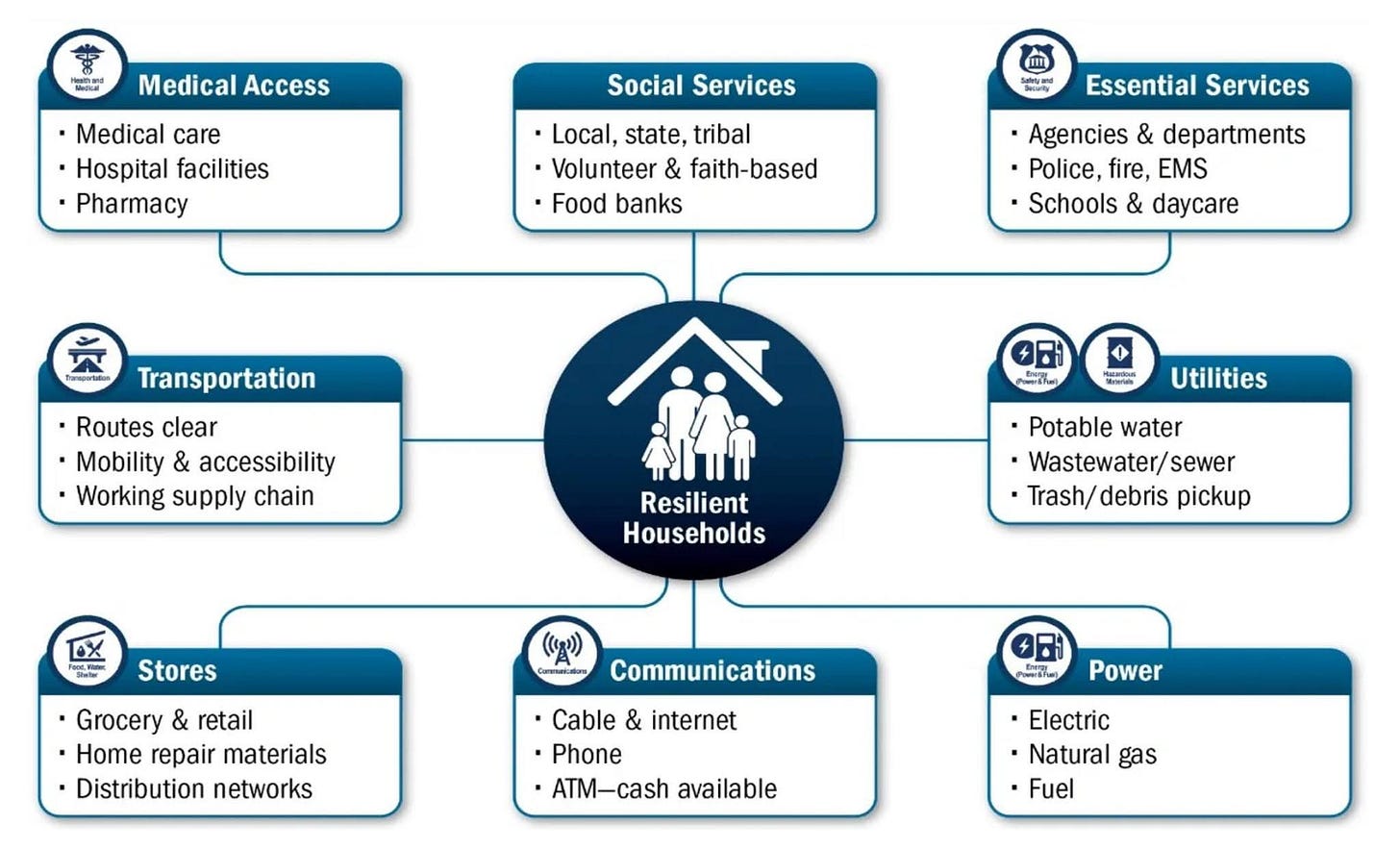

In the most recent evolutionary step, Emergency Managers have begun to embrace a Community Lifelines concept to guide their efforts in the emergency management cycle of Mitigation-Preparedness-Response-Recovery.

Interdependencies

It is here that I want to pivot back to where we began - talking about power and transportation.

Each of the eight Community Lifelines is critical for community resilience. It is my opinion, however, that two of them are supernal to the rest: Power, and Transportation.

Electrical Power is necessary for medical facilities and essential services to operate, for public utilities to function, for communications, food and fuel distribution.

Transportation is necessary for food and fuel shipping as well as emergency response access to the affected areas.

The other six Community Lifelines are inherently dependent on Power and Transportation.

Disaster’s Cascading Failures

No widespread disaster is defined by a key, single event, but instead through the speed and reach of the ripples introduced into the societal environment by that event.

Let us use this most recent Winter Storm as our case study: A large deposition of ice across a large geographic region

The First Ripple: Power, Water and Fuel

Power, water and fuel effectively remain invisible to our consciousness until they become inaccessible. Society accepts that power outages occur frequently, but generally with durations sufficiently short as to make them little more than inconveniences. And while the same could be said for our water supply (albeit with less interruptions), we rarely experience shortages in our fuel supply.

Of these three, electrical power is king: it is necessary to run the pumps of both water and fuel.

Rural and municipal water systems manage short-term power loss by maintaining system pressure via elevated water tanks, but those have a definable useful time before consumers notice a drop in pressure. When pressure drops occur under the umbrella of a widespread winter weather event, it is common for the community to quickly hoard water in bathtubs, buckets or jugs. This has the consequence of completely depleting any reserve or residual pressure in the system.

It is often that this first, dual-punch ripple of no power and no water starts what can later become a wave of public fear and panic. While fuel may not have yet entered the mind-eye of society, without electricity those who were hoping to ride the storm out with minimum fuel in their vehicles may now experience a slightly higher degree of fear.

The Second Ripple: Transportation & Logistics

The same ice that brings down power lines rapidly deteriorates driving conditions, and as we saw in Mississippi last week, can bring roads to a complete log-jam.

Anecdotally society knows that far-flung communities depend on ground transportation for goods and services. Unseen to the public eye is that most grocery stores maintain only about 3 to 5 days’ inventory of high demand, frequently perishable food items. Runs of food supplies are normal in the build-up to a winter storm, with some purchasing far more than would be needed, thus reducing availability for the larger community. When roads become impassable, food supply panic not unlike we discussed earlier regarding water becomes a reality. Retail management may be forced to temporarily close; it is not because of corporate insensitivity - it is because the supply chain is crippled.

Relief supplies & logistics such as generators, fuel, food and potable water are similarly stymied. No amount of increased volume of outcry from the public can make those supplies arrive any faster.

Essential workers such as healthcare, public safety and public utility operators similarly cannot report to their workplaces.

More Ripples: Communication, and Health

As power failures continue, secondary failures begin to manifest themselves through cell sites losing backup power, which itself results in rumor outpacing official information distribution because of network failures.

Community health is inexorably linked to consistent access to a safe, clean water supply, a means of managing sewage, and the removal of waste & refuse, all of which have root dependencies in power, transportation and fuel accessibility.

Final Ripples: The Human Element

Humanity and human decency are not listed among FEMA’s Community Lifelines, but I believe they are implied. The stress and strain of mounting, cascading issues such as have been outlined begin to manifest themselves within a few days’ onset of the crisis. Society may turn on those who are trying to help. This week I have heard of instances of residential internet providers being cursed mercilessly because service is out. Those responding are very often those living in or nearest the event, and are therefore ‘victims’ in the first-order just like everyone in the area, but are also at risk of becoming second-order victims of society’s growing dependence on convenience.

Threshold of Fragility

As society becomes more and more accustomed to, and dependent upon highly interwoven technologies, the gap between comfort and catastrophe narrows.

Technology allows us to combine many functions into single-point-of-failure scenarios. A few short decades ago if telephone lines went down, we couldn’t make a call. Today when communication networks go down, not only can we not make a call, we can’t pay for goods & services, navigate to shelters, verify a prescription or access health records.

Where information formerly flowed at the speed of television, radio and newspapers (and sideline: information was filtered and verified by the managers and editors of the same), today society demands real-time unverified updates. When data cannot be sent or received, the information vacuum can lead to an immediate sense of disaster - not that the situation has changed, but our ability to know about it has.

When we (and your writer certainly includes himself) lose the ability for our smart devices to send & receive information, or to even be charged enough to do so, we become effectively paralyzed.

While we have built better systems, we unconsciously built a dependency trap.

Resiliency is Redundancy is Resiliency

Where do we go from here? This winter storm did not surprise anyone with its approach and onset; it had been predicted for a week, if not more. While the details of those early predictions may have been nebulous or even fanciful in some cases, society was aware that something was coming.

Emergency Managers say that we should have at least three days’ worth of goods and products to get through a disaster. In reality, and based on my own personal experience through some 20 federal emergencies and disasters, we are better off by planning for 7 to 14 days.

There is an unstated message in that public education, however: NO ONE WILL COME HELP YOU for those three, seven or fourteen days.

In this article I have outlined very real instances where disaster relief simply cannot get to you, and I have witnessed it many times. I have also witnessed the aftermath when people did not take time to heed local, state and federal pleas to prepare or evacuate - often tragic aftermaths.

What can you do? Take stock of your daily life for a week. How many times did you use your phone, tablet or laptop? What did you use it for? How could those uses be divided up into less single-device dependent tasks? How much food, water, toilet paper, medication, laundry detergent….make the list as long as you wish….how much do you use in a week?

Take an honest inventory of those things and activities, then imagine how you would do the same but in a remote, austere camping environment that has no running water or electricity.

Resiliency is defined as the behavioral, emotional and psychological ability to adapt, recover or bounce back from adversity.

Redundancy is duplication to prevent failure.

By purposefully taking stock of your daily living habits, then taking steps to find ways to provide alternative means to support that daily living, you simultaneously bring yourself and family to a point of redundancy and resiliency.

We can’t control when the ice comes, or when storm winds howl. We can’t will a road blocked by ice, trees or stalled and abandoned vehicles to clear any faster than the laws of physics allow. The threshold of fragility is a choice we make daily when we opt for convenience. Moving that threshold requires a shift in mindset from assuming someone will help, to knowing you are ready. We can control the margin of error we provide for ourselves. In building that safety net, we stop being helpless witnesses to cascading crises and become part of the solution.

Those things lessen the fear and panic we talked about many paragraphs ago.